As I write this, I have just started studying using Shinkanzen Master N1 (新完全マスターN1), after having finished the N2 series (and learning that the JLPT exams in the UK are cancelled this year - again!), and was reminded as I went to buy my new textbooks that it has been just under a year and a half since I ordered my copy of Genki 1, and just about one and a half years since I began considering studying Japanese at all. With this in mind, I thought it might be a good time to reflect on what I’ve learnt so far, what resources I’ve used, things I enjoyed, and what I would do differently if I could start again from scratch. There have been a million posts on this subject before me, and there will probably be millions after, so take this as one experience and opinion in a sea of many (probably more qualified) opinions!

Before we get to hard statistics, I’ll chronologically walk through what resources and methods I used through my learning process, and whether they ended up working out for me personally or not. Beginning with possibly one of the most ubiquitous beginner series out there—

Genki

Knowing quite literally nothing about the language other than it’s native name, I ordered “Genki 1” after a mildly thorough Google expedition to find recommended Japanese textbooks for absolute beginners like myself. A countless number of sites, videos and podcasts will recommend Genki as the premier beginner resource for people starting with Japanese - and I can’t say I disagree. Coming from someone who, bearing in mind, does enjoy using textbooks in daily life, it was an easy transition to make into starting a regular, consistent study schedule, rather than relying on app notifications or daily quotas to try and keep me motivated.

I had previously tried using Duolingo to learn an unrelated language a few years prior to picking up Genki, likewise later on with Busuu for Japanese, and my experience with them was very mixed. As many others before me have noted, Duolingo’s general course structure for Japanese, and quite a few of it’s other community-sourced languages, was severely lacking at the time that I was an active user (although I can’t speak for the present day). In addition to this, the sole fact that sites and apps like these are on a mobile platform, which may be a great benefit to some, was most certainly not to me. Distraction is all too easy when you can simply double tap the home row and disappear into any of the other apps you have open, and studying isn’t exactly the most thrilling activity in the world, no matter how dedicated you are to your development. Having a physical textbook like Genki was certainly of great use to me, as it meant I could disconnect from everything else I had going on, sit down, and just ‘study’ for an hour.

As for the actual contents of the textbook, they were actually surprisingly interesting for what I had assumed would be a fairly classroom-style dry tome. There’s a consistent set of characters which interact with each other and progress a story, even if completely mundane, as well as a cheerful (you could even say 元気, har har) set of illustrations that genuinely increased my enjoyment of the book over my time with it. The explanations of grammar points were also quite easy to understand and pick up, as an English native speaker at least, although their explanations of the passive and causative forms was quite poor, and is one gripe I still carry with me from these books as it led me to a fair few misunderstandings down the line.

It was certainly good enough to keep me on the hook through Genki 2, which I purchased in early February of 2021. At this point I was studying for one hour a day, as well as completing Anki reviews (which I’ll talk about after this section), which led me to finish the Genki series (books 1 and 2) in 268 days, or 8.8 months.

Anki

Image courtesy of Tejash Datta.

I started using Anki via. the open source AnkiDroid app for Android at roughly the same time that I started studying with Genki 1. It had been recommended from a random YouTube video I was watching on the topic at the time, and also from one of my friends who began studying at a similar time to me. To be honest, I can’t quite remember the actual trigger that made me try it out, but I downloaded it, made a deck, and started adding cards from Genki’s first lesson.

Originally, I tried using a pre-built “Top 2K Common Words” deck, but was quickly bored out of my mind. Here’s the thing, for me, Anki isn’t fun. Looking at the statistics certainly is, but the actual process of going through card repetitions is definitely not something I actively enjoy. I don’t know if it’s actually “fun” for anyone, it’s quite a tedious process. The main enjoyment that I get out of Anki is seeing a card come up that I can remember the context and meaning for, and can then immediately answer, which is an experience I would never have had with a premade deck (at least in my case), since at the time I was just going through Genki and not consuming much of anything else.

I began adding words from the “vocabulary” sections of all the Genki lessons I was working through, and it worked out surprisingly well. Anki, for all of its faults (and there are a few) is a very effective memory tool, as advertised on the box. My original card limit was something like 10 new cards a day, however this quickly became 15, then 20, and now sits at 25 cards a day as I write this. Really, I don’t see myself raising the limit any further, as I already have enough Anki review time as it is, but that works out to be a comfortable amount for me as I only make a very small subset of cards. Here are the types of cards in my deck:

- Single word cards (Japanese -> English) If the word has a kanji form, then the kanji form is written on the front side of the card, and the hiragana reading is also on the flip side.

- Grammar sentence cards A single example sentence that uses a piece of grammar I’m trying to learn. On the reverse side is the English meaning of the sentence.

That’s it. Yep, no sentence cards, no audio cards, no media at all in fact. For me, it works. I know many others in the community love to use sentence cards from the media they’re consuming to learn new words via. Anki, but personally I’ve been using just single word translation cards & grammar sentence cards, and it’s worked well for me thus far.

Obviously those types of cards on their own would be nowhere near sufficient to get you up to a high level of proficiency, but when was Anki ever supposed to be a main source of learning? At least personally, I see it as purely a supplement to whatever reading, watching or other form of consuming the language you’re doing as well.

I’d like to share some Anki statistics with you all, but I’ll wait until the wrap up at the end for that.

Tobira

After finishing the Genki series of books, I was quite nervous about what I should continue doing afterwards now that I’d built up a bit of grammar and vocabulary knowledge. To that end, I spent a considerable amount of time researching what textbooks and other resources were available, whether this “immersion” thing that everyone and their dog was recommending was worth it, or whether I should just throw myself into the nearest river.

In the end, I chose Tobira.

Tobira is a textbook that is very unlike the first two Genki books, and likewise not too similar to the defacto follow-on from those books, Quartet, also published by the Japan Times. It is written entirely in Japanese (albeit with furigana, thankfully), and attempts to avoid using English within the book wherever possible, which was the main factor in my decision to use it as my follow-on from Genki.

It forces you to get accustomed to reading purely in hiragana and kanji, and if that’s something you haven’t done prior to starting the textbook, it can feel quite overwhelming. In my case, I found the first lesson quite difficult to work through having not really read much in purely Japanese before this point, however after working through a single lesson over a few days it became exponentially easier from then on to understand.

In addition to this, it also gives you lengthy passages from real texts as well as ones authored by the Tobira writers to test your reading and comprehension ability of the grammar that it taught you in the lesson preceding, which comes in a variety of genuinely interesting forms. For example, there is a lesson which has a manga section describing the invention of Cup Noodle, which I found quite amusing.

Had I continued on with Quartet or another majority English-based textbook, I suspect my Japanese reading skills would have been much worse off than they are now.

That isn’t to say there aren’t downsides to the textbook, one being that their grammar explanations compared to the Genki books felt quite lacking in substance. In the Genki series, you would get maybe a third to half a page per grammar point, explaining the basic usage, then nuances, and providing plenty of example sentences/diagrams to aid in understanding. In Tobira, you get an equation showing the correct form, a couple sentence explanation of the grammar point, and then two or three example sentences.

Overall, I thoroughly enjoyed my time with Tobira, however. The different stories and articles that were presented in each lesson were the first time in my Japanese textbooks that I was genuinely interested in reading the contents of the practice sections, rather than just for the sake of improving my comprehension.

I finished Tobira in 120 days, or 3.94 months.

Wanikani

© Tofugu, LLC.

During my time with Tobira, I also tried another quite popular service for learning kanji and vocabulary, “Wanikani” by Tofugu (yes - the blog people, their site is pretty great, you should check it out). I started a monthly subscription to try it out, and by the end of two months, I had cancelled my subscription.

That’s not to say it’s a bad service, the native recordings, mnemonics (even if I didn’t use them) and interface are all lovely despite my grim opening paragraph, there were just a few key issues with the service that I couldn’t surmount in order to use it effectively, or have fun using it much at all. Chiefly, the fact that everyone starts from level zero.

This is a great thing for beginner learners, as it means they can build up their vocabulary from the very bottom learning the mnemonics and readings as they go, however for someone who was already a good way through Tobira, having to go and sit through repetitions of “本”, “川” and “用” over and over again was mind-numbingly dull.

In addition to this, you have no way to speed up the content you receive, so you’re stuck with a slow trickle of content that, if you were in my scenario, you already many moons ago learnt and internalised. Your monthly subscription will have dragged on for quite a while before you actually start seeing any new information, so you’re essentially paying for a recap. This isn’t exactly an ideal user experience for someone trying to enter somewhere other than the ground floor, and I don’t think too much thought has been put into this use case.

But that’s Wanikani’s decision to make, and if they’ve decided that intermediate learners aren’t the demographic they’re trying to aim for, then that’s unfortunate, but a decision I’ve got to respect. Some services aren’t for everyone, and Wanikani in its current state certainly isn’t for me.

Shinkanzen Master N2 & N1

The next step I chose from Tobira was a series that up until that point I had seen, but not touched - The Shinkanzen Master series, published by 3A Network. These span the entire range of the JLPT spectrum, all the way from N5 to N1, however they’re not a particularly heavy contender in any of the categories of the textbooks I’ve mentioned previously, namely the N3-N5 range. The reason for this becomes fairly apparent when you start using the books, and it’s simply because - yes - they’re incredibly dry.

In comparison to some of the more fun and lighthearted content coming from books like Tobira with their small manga comic strip in one of the lessons, and the recurring characters throughout Genki, Shinkanzen Master has a distinct lack of charm and style. Even the covers of the books let you know it’s not exactly going to be a thrilling ride, take a look for yourself:

What’s with the mustard yellow?

© スリーエーネットワーク出版社

However, for all the bashing I can do about the lack of anything interesting inside this series of books, one thing I can’t dispute is they’re solidly written, comprehensive textbooks. They cover all the required grammar points for each JLPT level, and have a wealth of questions for both reading comprehension, listening comprehension and vocabulary, as well as a kanji reference for the given JLPT level if that’s something you’d consider using. The grammar points are (the large majority of the time) well explained, and the introductions of each section of the real exam and how they relate to what you’re being shown in the textbook are superb.

They might not be a gripping read, but they will certainly help you prepare for the real thing, if your aim is to end up taking one of the JLPT exams at some point in your learning journey.

Most of the complaints I have with these books stem purely from the practice question portions, more specifically from the grammar practice answer booklet. In the main textbook body, there are questions that are intended to make sure you’ve understood the grammar point introduced in the lesson just prior, and every 4 lessons as a recap of the entire previous collection of grammar points, however the answers to these questions often fail to give a reason as to just why that answer is correct.

This is fine in the majority of situations, as often it’s clear what the mistake in the other answers is once you’ve seen the correct solution, and you can refer to the grammar point explanation in the lesson to see why the other answers are incorrect. However, a non insignificant amount of times during my run through Shinkanzen Master N2 (and also N1, which I’m working through at the moment), there have been questions where the only differentiating factor between answers is some very small nuance of the grammar point. In these cases, even upon re-reading the grammar explanation and included caveats, I cannot distinguish why the “correct” answer is any more correct than one of the incorrect answers I’d mistakenly put down, leading me to have to dig down an online rabbit hole or pester some online friends as to what exactly the nuance is there.

Certainly a minor gripe, and certainly a problem that can be solved by simply seeing the grammar point appear in real content later down the line, however it would be (in my opinion) incredibly useful to include a small explanation as to why the incorrect answers are wrong, at least in some of the more difficult to discern cases.

Immersion Materials

Something I haven’t really mentioned so far are the things I’ve been using to “immerse” with for learning the language outside of traditional study resourcese like I’ve been writing about so far. It should be obvious by this point, but native real-world Japanese materials are very often far more valuable and important to language development than simply sitting in front of a text book, in balance of course.

I’m of the opinion that both are useful in their own way, and that splitting your time between traditional study and “immersion” is something that will help immensely. The word “immersion” has, at least for me, been partially ruined by the Japanese language learning community at large, mostly thanks to the nebulus hyper-immersion focused brigade, which I imagine would audibly scoff at the mere mention of using a textbook, let alone recommending one to beginners.

Obviously this is a very small subset of an otherwise I’m sure lovely community of people, however “one bad apple spoils the bunch” is a proverb for a reason, and in this case the apple is very loud, opinionated and terminally online. To sum this unnecessary foreword up, use whatever balance of textbooks and native content you feel comfortable with, and you’ll find the right balance eventually.

With that out of the way, here’s a quick list of “stuff” that I’ve consumed since I began consuming native content properly, some time around the N3 level.

Anime

This list is in as approximate as a watch order as my failing memory could provide, but the difficulty roughly scales upwards as you go down the list. There are a few exceptions here and there, as I used jpdb.io’s Anime List to determine what would be appropriate for my difficulty.

- Flying Witch

- Orange

- ReLIFE

- ReLIFE Kanketsu-hen

- ニセコイ

- ニセコイ:

- Fruits Basket 1st Season

- Fruits Basket 2nd Season

- Fruits Basket The Final

- 境界の彼方

- 劇場版 境界の彼方 I’LL BE HERE 未来篇

- ホリミヤ

- かぐや様は告らせたい: 天才たちの恋愛頭脳戦

- 聖女の魔力は万能です

- ヲタクに恋は難しい

- 斉木楠雄のΨ難

- 斉木楠雄のΨ難 2

- 斉木楠雄のΨ難 完結編

- Cowboy Bebop

- 映像研には手を出すな!

- Planetes

- Death Note

- Psycho-Pass

Podcasts

I mostly used podcasts on my morning and evening commute, which was about two hours each day, to try and cram some listening in during working hours. At first I mostly listened to 日本語コンてっぺい, however as this became quite easy to understand and I was picking up less vocabulary, I switched to mostly listening to 4989 American Life to increase the difficulty factor.

I stopped listening to podcasts during my commute at roughly N2 level. Not because it wouldn’t still be effective, there were simply other things I wanted to listen to.

Books

I began seriously reading books in December of last year, as I felt my level had finally progressed to the point where reading a novel wouldn’t melt my brain. The list here is in chronological order, and zigzags in difficulty a tad - I wouldn’t say any of them were particularly ‘standout hard’ apart from “69” by 村上龍, which took a bit more thinking than I’d like to admit.

- 冬野夜空 - 一瞬を生きる君を、僕は永遠に忘れない

- 汐見夏衛 - 夜が明けたら、一番に君に会いに行く

- 新海誠 - 秒速5センチメートル

- 住野よる - 君の膵臓を食べたい

- 米澤穂信 - 氷菓

- 村上龍 - 69

Manga

Before I started reading books at the end of last year, I was instead reading manga, as it was generally a more appropriate level for the comprehension I could muster at the time. Generally avoiding solid blocks of prose, and having a wealth of visual hints, they were ideal for me as a beginner reader, however I don’t really read manga apart from just “for fun” at the moment (particularly ホリミヤ - I dropped the rest).

Games

In the past, I’d frequently played games in English, so when I began considering reading proper novels I also started playing some games I’d previously enjoyed in English (and some new ones) in Japanese too. Mostly visual novels, and entirely Japanese-developed games.

These vary wildly in difficulty, and I didn’t really play them in any specific order, so don’t expect a nice curve to come out of these.

Statistics

Just before I round off this retrospective, I thought I’d include a section with some interesting and amusing statistics about the time I’ve spent with Japanese so far. To begin with, as hinted earlier, I’ll share some of my Anki statistics with the world.

Anki - Card Totals

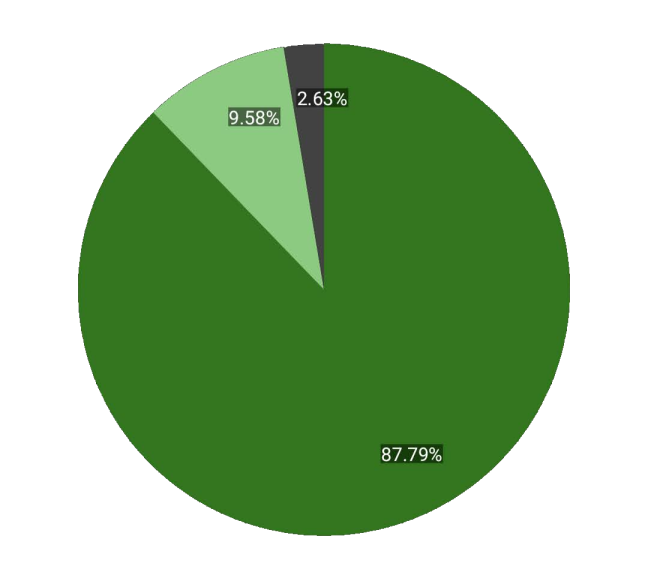

In the 1.5 years that I’ve been using Anki, I’ve added 9851 cards to my main deck, not counting my pitch accent deck. This is roughly 17.5 cards/day, or 122.5 cards/week. From these cards, 8648 (87.79%) have reached “Mature” status (meaning their interval is larger than 2 months), 944 (9.58%) are in “Young/Learning” status (meaning their interval is between 1 day and 2 months), and 259 (2.63%) I have never reviewed before.

My time spent on Anki currently clocks in at 11,802 minutes, or 192.7 hours. This is equivalent to roughly 8 continuous days, which sounds like a lot until you consider that actually, that’s only 22.9 minutes a day for the days that I studied.

Anki - Repetition Data

In terms of how frequently I actually studied my repetitions during this period, I completed my reviews on 515 days out of 562, or 91% of days. This is largely because when I started Anki my study habits were not properly in place, and I would frequently miss days and drop cards. If you take a sample from the last year, I have studied 365 out of 365 days, 100% from the last year.

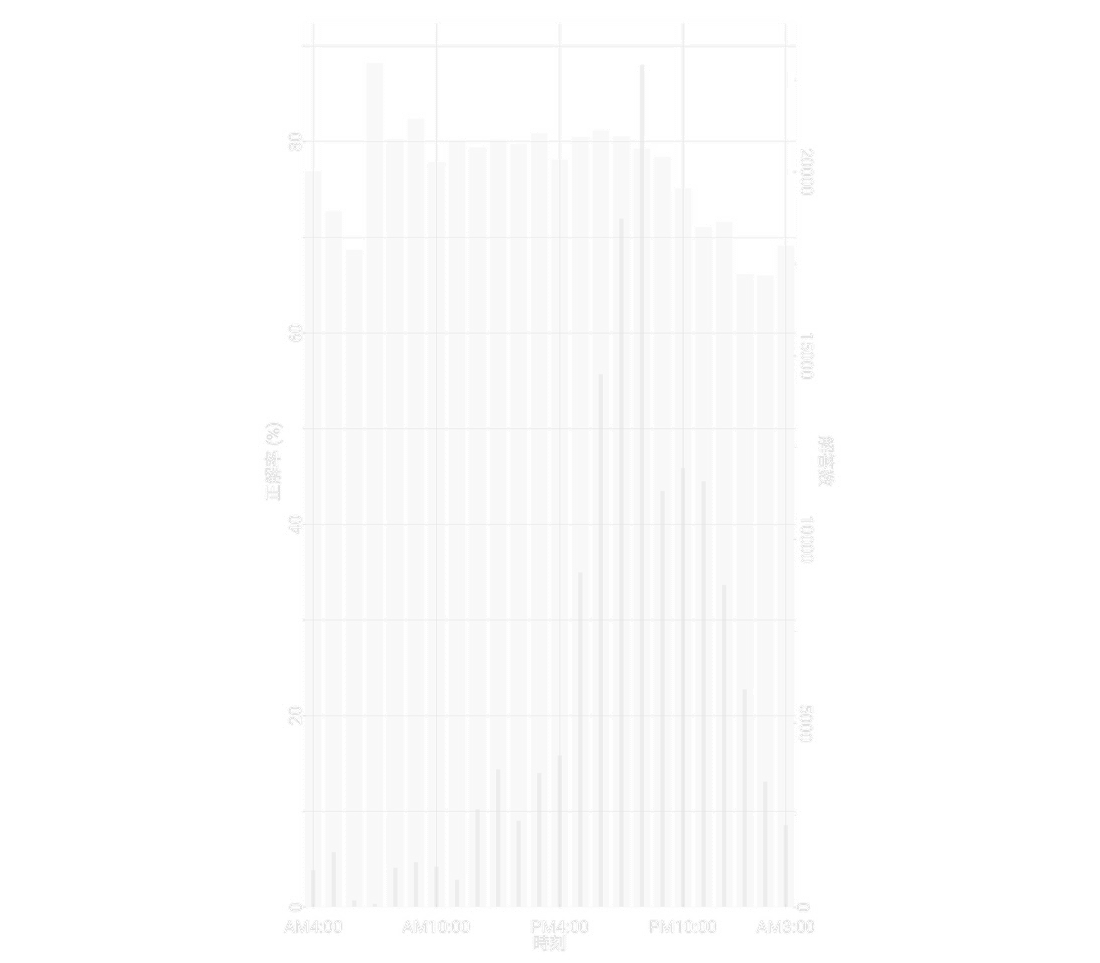

If we separate these study sessions for time you can see the following frequency and recall percentage graph. The thin white bar is the frequency of reviews, measured from the right hand axis, and the semi-transparent grey bars are percentage correctly recalled, measured by the left hand axis. Besides the embarassing amount of reviews at ridiculous hours, you can see a clear trend downwards in recall rate starting from roughly 6PM onwards, which is evidently when I’d begin to get tired. The blip upwards at 7AM can safely be ignored as an outlier, since there were practically no reviews performed in that time frame.

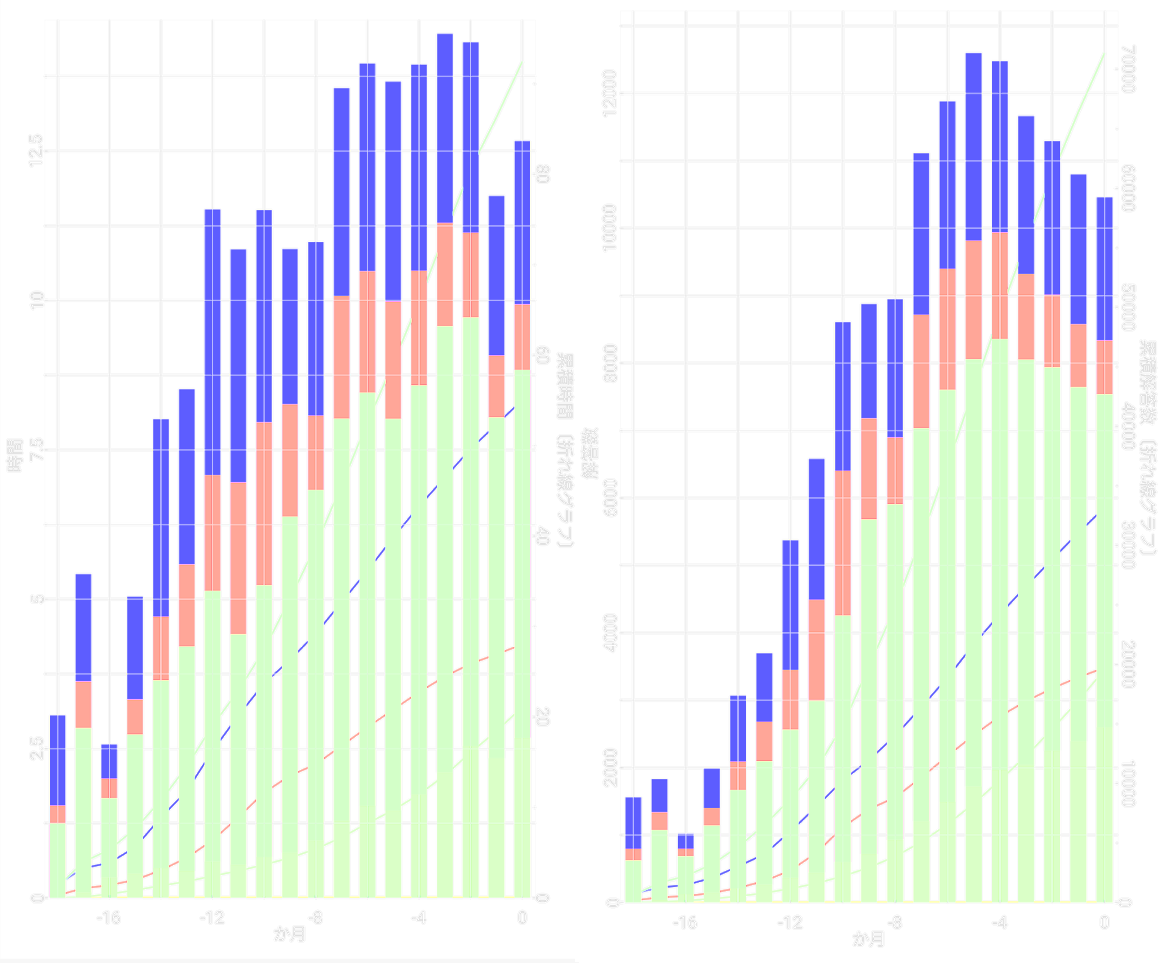

Anki also allows for plotting the total number and time spent on reviews over time, as seen in the above two charts. The chart on the left shows the amount of time, in hours, I spent on Anki each month, and the right hand chart displays the number of cards I reviewed per month. The lines behind bars represent a cumulative total, read with the right hand axis.

As you can see, the number of cards I reviewed each month was at an exponential-ish pace for the first year and a month of my Anki journey, however began declining after this point down to the current level, where it is unseen whether it will decline further. So, why the decline in reviews? I’m still doing the same (uncapped) amount of recall repetitions per day, and have been consistently learning 25 new cards a day since around 8 months ago (you can see this is where where the blue bar becomes the current fixed size).

My theory for this is that from the point at which I fixed the new unlimited number of reviews and 25 learned cards a day, I have improved the rate at which I answer cards correctly (as you’ll see below in a minute), which has lead to me having to perform less incorrect reviews for any given day, and then also in turn less re-review in the short term from less card intervals being reset. This can be seen fairly well in the chart, as you can see the shrinkage in the bars’ red zone area approaching the current day.

In terms of the time that I’ve spent per month (left graph), it has been quite sporadic, evening out until around two months ago, at which point it then drastically dipped to pre-8 month ago levels. The jump in time that you can see at around the 7 to 8 month mark coincides with when I changed my card review count to unlimited, which explains this bump. You can also see a significant time bump at 12 months ago, coinciding with when I increased the number of cards I was learning from 15 to 20, and then fairly quickly from 20 to 25.

The reason for the sudden drop in time spent two months ago, despite keeping the same settings for everything since 8 months ago? Frankly, I have no idea, although it does, perhaps coincidentally, coincide with when I first began reading novels properly. How this links to my time spent, if at all, I have no idea.

Anki - Card Recall Efficiency

My total review count over the one and a half year period was 143838 cards, or 279.3 cards reviewed per day on average, for the days that I actually reviewed. On each card, I spent an average of 4.9 seconds, the percentage of which I got correct are as follows:

- I successfully recalled 62.81% of “Young” (学習中) cards.

- I successfully recalled 82.88% of “Learning” (定着中) cards.

- I successfully recalled 94.96% of “Mature” (定着済) cards.

These stats are, again, slightly skewed by the fact that at the beginning of this period I was simply not used to both the way Anki worked, and my brain going through the reviewing process in general. If we take the statistics for the last month, it shows a slightly different picture:

- Last month, I successfully recalled 72.00% of “Young” (学習中) cards.

- Last month, I successfully recalled 89.98% of “Learning” (定着中) cards.

- Last month, I successfully recalled 95.54% of “Mature” (定着済) cards.

Here you can begin to see where the Anki algorithm breaks down. Despite large improvements in both the “Young” and “Learning” categories, the “Mature” category sees an almost negligible improvement of roughly 0.6%. As intervals become longer, Anki seems to find it more and more difficult to calculate the accurate time to refresh your memory on a given card, leading to an upper cap on this particular category.

Anime - Watch Statistics

In total, I have watched 486 episodes of anime, totally around 6.6 continuous days of watch time. This was over the span of 24 TV broadcast anime, 1 OVA, 3 movies and 2 special episodes. The average rating I gave to these was an 8.

Books

This is going to be a fairly underwhelming section since I only started reading around December last year, however I’ll give some brief statistics here to round out the section. In total so far I have read 6 books, of which 5 have a countable word count (I can’t seem to find a count for how long ‘69’ is, unfortunately). These countable books contained a total of 417,294 words, with an average sentence length of 20.65 words. The highest difficulty book that I’ve read so far, according to JPDB, is 氷菓 with a difficulty rating of a 6/10, although I’d judge this as markedly incorrect since ‘69’ is missing from their database, which is in my opinion a clearly more difficult read.

Conclusion

Over my one and a half years learning Japanese (now slightly over seeing how long it took me to finish writing this), I’ve gone through many a resource: some good, some mediocre, and some that were so downright terrible that I didn’t have the finger energy to waste typing them out in this retrospective (looking at you, GooDict).

The main thing that I took from this experience, going through all the previous tools I used to get to the current day, was that there seems to be no ‘correct’ or ‘optimal’ path to take for learning something like a language. Sure, there are more and less efficient ways of doing it, and picking a drastically wrong path will lead to it taking a very long time indeed, but you’d have to pretty far off course with how many resources and pointers are available online today, even compared to 5 years ago. In my opinion, if you want to learn Japanese (or any other language for that matter) as efficiently as possible, pick any study method that looks appealing to you, and go.

You might find out that study method sucks a few weeks or even months into using it, but that’s completely fine. At least some progress was made, and you now know what sort of thing doesn’t work for you, and can now accurately choose a path that will inevitably be more effective. On the other hand, if you try and immaculately optimise your study right from the start, analysing every commercially available tool and resource, and balancing the exact difficulty of all the content you’re consuming word by word to craft a perfect difficulty curve, you’ll end up spending all of your time studying ‘how to study’ rather than actually doing the studying itself, which is something I’ve definitely been guilty of.

It’s been an interesting one and a half years, and it will hopefully be a further interesting one and a half years until I hit the three year mark. I’m hoping to take the N1 in December of this year after completing the Shinkanzen Master N1 series (and doing some exam preparation - yikes), at which point I might finally have something to stick on the wall and say is a concrete achievement from this endeavour, however I already feel immensely satisfied with the progress I’ve made thus far, and am looking forward to seeing what point I’m at in a year or two years’ time. I’m planning to make another one of these posts at the three year mark, and it will be interesting to compare it to this post when the time comes.

In addition, I am going to at least attempt setting up a posting schedule for this blog so that there is a steady stream of content, be it to do with the media I’m interested in at the time, or just general learning ‘stuff’.

Either way, thank you for reading, and the best of luck with your studies.